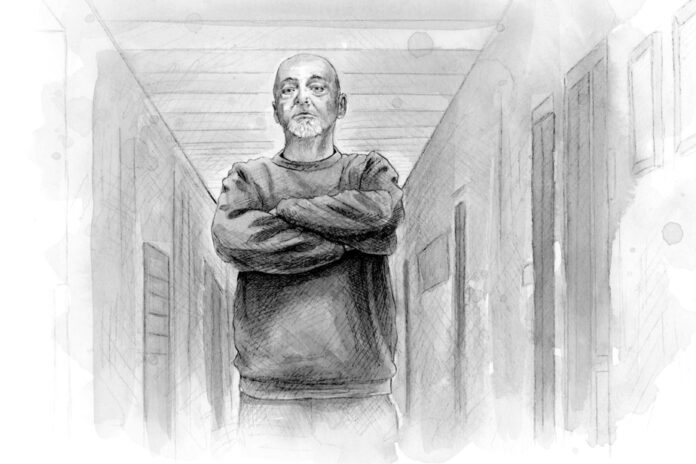

The man in front of me, in the small room of the Montée Saint-François penitentiary, has been imprisoned for 30 years. Arrested in 1992, then convicted of a quadruple murder, Daniel Jolivet could have been eligible for parole in 2017. But for that, he would have had to confess to having killed these four people.

“Sometimes an inmate says to me, ‘Why don’t you confess, you’ll get out?’ I answer him: “Why don’t you confess to these crimes? Because you didn’t? Well, I didn’t do them either. »

To prove it, he wrote everywhere, requested thousands of pages of documents, reconstructed the fabric of events, memorized everything… In the hope – and despair – of finally being heard.

A legal columnist at the time, I remember this bloody crime of November 1992. His conviction and the legal adventures that followed. I especially remember the calls to the newsroom in the early 2000s from this man in his forties who explained how he had been the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

His lawyers put together a huge file to prove his innocence in 2005, then came back to the charge twice with the federal authorities. Each time with new elements which demonstrate at the very least that the trial of this man was not “fair and equitable”, according to the established expression.

With screenwriter Daniel Proulx, I did a program on this affair on Canal D in 2008. Ten years later, Isabelle Richer devoted an episode of Enquête to Radio-Canada, then a podcast.

And now in 2018, a scientist specializing in belugas between two contracts, Pierre Béland, became passionate about the case. He searched, investigated, hired detectives, and finally wrote a book to be published next fall to demonstrate that a miscarriage of justice was committed. He is deeply convinced of this. “Everything Daniel told me, about every detail, is true. »

Daniel Jolivet is now 65 years old. He was 35 when he entered prison on November 14, 1992, and was to be married the next day in Mexico.

This is not what is called an “upright citizen”. Even before he was arrested for those four murders, he had spent a good part of his adult life in prison.

Born in Pointe-Saint-Charles, of which he knows “every nook, every corner”, Jolivet is the son of a taxi driver father who also served time in prison.

“It seems like it was in our blood, it’s funny to say that… My mother raised us alone, she cleaned, she worked as a butcher at Eaton’s. We weren’t watched that much. I was hanging out with guys who were doing shots. I started flying when I was 12, 13. They sent me to Mont Saint-Antoine [a center for young offenders]. »

As he got older, this “peaceful” was increasingly consorting with kingpins, and handling weapons, not for hunting.

This is also the fact of almost all the important witnesses in this case.

The essential facts take place in less than 24 hours and seem very simple: thieves, drug traffickers, a settling of accounts which results in four victims…

There is no DNA evidence, a fingerprint, a mystery witness that would close the debate. Several of the “new elements”, taken in isolation, are not sufficient to demonstrate the innocence of Daniel Jolivet. But the sum of disturbing details that accumulate before our eyes ends up making a mountain that far exceeds the famous “reasonable doubt”.

Louise Leblanc knows it. Something happened. It is not normal.

Even when he is very busy, his brother always answers his emergency calls – the code “911” sent to his “pager”.

But this November 10, 1992, she has the “pager” again and again: nothing.

It is 6:30 p.m. when she decides to go see for herself what is happening. She takes her 13-year-old daughter and drives to her brother’s house.

François Leblanc lives on the ground floor of a luxury condo building by the river in Brossard.

Louise sees her brother’s car in the parking lot. But also that of his girlfriend, well, his ex-girlfriend: Katherine Morin.

She rings. Nobody’s answering. Louise Leblanc and her daughter walk around the building. Through the French window, they see that a plant is knocked over on the ground. Odd. Rising on tiptoe, Louise Leblanc sees, further in the apartment, the body of Katherine, lying on the ground.

Louise Leblanc immediately thinks that the 20-year-old woman passed out due to her pregnancy – it was later learned that she was not pregnant. She herself had experienced fainting spells during her pregnancy.

She runs to call Katherine’s parents on a public phone (cell phones are still a rarity). She tells them to call an ambulance.

In the meantime, she runs to get the concierge to open the apartment. He doesn’t have the key: the lock has just been changed.

Maybe we can go through the French window? suggests the concierge. Impossible, we’re wasting our time, thinks Louise Leblanc: her brother always locks his doors. She knows he is suspicious. Because. Officially, Leblanc works for a cell phone dealership, but she suspects that he has other activities. She’s seen guns in his house before. He always tells her, “Don’t ask questions if you don’t want to get lies.” »

François had known Katherine the previous winter. They had been dating for a few months. She had even lived with him for a time. They had broken up and resumed a few times, before she returned to live with her parents.

Louise Leblanc had ended up befriending her “sister-in-law”. So much so that the day before, November 9, the two women had had supper together. Katherine knew that François had recently been dating another woman. She wanted to know who it was.

After supper, Louise Leblanc had agreed to drive her that evening to her brother’s house, so that she could go and confront him, without warning. His new girlfriend was there. Leblanc quickly dragged Katherine outside to explain herself. After about fifteen minutes, she left, sad and angry, with Louise who witnessed the scene hidden behind a bush.

All evening of November 9, Katherine wanted to call François back. Resume the conversation. Tell her she was pregnant.

She called another acquaintance, Christina Piro, at 11:00 p.m. to tell her that she would return to confront him: he could not leave her for another when she was expecting (she believed) a child from him!

Piro told him not to.

But two hours later, after 1 a.m., Katherine called Piro back. She was determined, she would go to the condo immediately to see François. Too bad.

Christina was convinced she wouldn’t go, it was so late…

That was the last news we had from Katherine Morin. She had not returned to her parents during the night of the 9th to the 10th. They had called her on the morning of the 10th. Then all day. Without success. They wanted to call the police, but Louise Leblanc convinced them to wait: she was going to take care of it.

Louise Leblanc is therefore with her daughter and the concierge wondering how to enter the condo while waiting for the ambulance, called for what is believed to be the fainting of Katherine Morin.

The janitor tries to open the French window. We never know. Oh… She’s slipping. He freezes. He asks the woman to enter the apartment with him. The two move forward into the silent condo.

They see blood around Katherine Morin’s head. The janitor shouts, horrified. The two exit, in a panic. But not the teenager. She walks into the apartment. It is she who discovers a little further the body of her uncle François, in a pool of blood. Then that of another young woman she does not know, also lifeless.

The Brossard police arrive quickly. They learn on the spot that this Leblanc works for a certain Denis Lemieux, who lives in the same building, on the sixth floor.

Ostensibly, Lemieux runs the “Cantel” telephone branch for which Leblanc works, in Laval.

In reality, Lemieux, 49, is a major drug trafficker, already sentenced to 14 years in prison. Leblanc, who is 31, is his lieutenant. Lemieux gives the orders and Leblanc takes care of the details of distribution and collection.

The police are quick to find Denis Lemieux also dead in his apartment on the 6th. He was killed from behind, like Leblanc.

According to pathologist André Lauzon, the murders date back to the previous night. Lemieux was murdered after the other three, according to the medical examiner.

Katherine Morin was 20 years old.

Nathalie Beauregard had just turned 23.

The police tell reporters that this is a settling of scores against Leblanc and Lemieux. The two young women were “in the wrong place at the wrong time”, they say: shot because they were unwitting witnesses.

There is talk in the newspapers of an attempt to seize a hoard which would have turned into carnage. Some make the link with the assassination, a few hours earlier on November 9, of the boss Roger Provençal. Western gang? Mafia? Lemieux had been associated with the criminal milieu for a long time.

The investigation is not dragging on. Three days later, on Saturday November 14, Daniel Jolivet and Paul-André St-Pierre were arrested and charged with the four murders.

The murder weapon had not been found. Nor fingerprints of the accused. The reddish stains believed to be the blood of the victims on Daniel Jolivet’s clothes were not. And there were no direct witnesses.

The evidence on November 14, 1992 rested on three pillars.

Two witnesses had spent several hours the day before the murders with the defendants. They had met the defendants at a meeting in Laval with two of the victims, traffickers Denis Lemieux and François Leblanc. They then followed Jolivet by car to retrieve machine guns belonging to Leblanc. These two witnesses said that Jolivet wanted to use the weapons to get rid of his job givers, Lemieux and Leblanc. That he had become paranoid and wanted to burn out: kill them and get away with the cocaine they were controlling.

Pillar Two: At a time when cell phones were still a rarity, telephone communications and their pick-up by towers suggested that Jolivet was at the crime scene around midnight on November 9, and possibly later that night. 10, that is to say at the time of the crime.

This witness is called Claude Riendeau, an ex-policeman who went wrong.

Before becoming the star witness against Daniel Jolivet, Riendeau had been an informer for the first time, five years earlier. Involved in an armed robbery which had turned into the murder of a police officer, Riendeau had turned his back and testified against his accomplice.

In 1992, the ex-cop did it again, this time against Jolivet.

To defend himself, Daniel Jolivet had not chosen the last comer. Léo-René Maranda was one of the most famous defense lawyers in Montreal.

Me Maranda had already defended Jolivet, just a few weeks earlier, in a case of gunshots in a bar – the Salsathèque. Someone had identified Jolivet as the author of these warning shots which did not cause any injuries. But the witness quickly relented, and the case was quickly dropped.

In principle, nothing more logical as a choice than Me Maranda.

Two details, however, made the police wince. First, how could Jolivet, a not-so-great criminal, afford Maranda’s services?

But above all: how could Maranda defend in court a man accused of having murdered… his own client?

The trafficker Denis Lemieux was indeed a client of Me Maranda.

More: Lemieux and his wife, Monique Brunelle, were dating lawyer Maranda and his wife, Andrée Marquis.

When Lemieux was murdered, his wife was at his sick mother’s bedside in Florida. Returning in disaster, she was hosted by the Maranda-Marquis couple – her condo had become a crime scene.

And now he was defending the man accused of shooting the husband of this woman who lived at his house?

Initially, the Crown raised no objections.

It was 1992, and the obligation for the police and the prosecution to provide all their evidence in advance was still very new: the famous Stinchcombe decision had been handed down in 1991 by the Supreme Court. A charge could now be dropped if the prosecution had not provided all of its evidence to the defense in due time. The records provided several examples of wrongful convictions where the police concealed evidence favorable to the accused.

This case was one of the most serious, if not the most serious, of his career, and he had no intention of escaping it. He therefore kept to himself a whole series of information unfavorable to his thesis.

From the outset, and repeatedly, attorney Maranda reported that he had not been provided with an interrogation, the name of a witness, wiretapping, tailings reports, etc.

Thirty-five years of practicing criminal law had taught him to distrust the police. But he had no idea how much would be discovered, and how much would be destroyed, many years later, and long after his death.

Always meticulously prepared, he practiced the art of police cross-examination like no other. With his hoarse emphysematous voice and a broom mustache that permanently concealed a sarcastic half-smile, he could spend days dissecting and dismantling piece by piece the testimonies that were a little too smooth, a little too sure.

We were only at the stage of the preliminary investigation, which consists of summarily exposing the evidence to see if it justifies a trial. The exercise spanned six months.

Unsurprisingly, Jolivet and his co-accused, Paul-André St-Pierre, were sent to trial for two first degree murders and two second degree murders (not premeditated). The prosecution’s theory was that the defendants had planned to go and liquidate Lemieux and Leblanc, but not the two young women.

I say “unsurprisingly”, because at this stage we are not looking at the quality of the evidence; the judge only notes its existence.

The real fight would take place at trial, before a jury.

But Jolivet was going to have two very bad surprises long before.

As the crime appeared to be related to drug trafficking, and as Maranda had defended the victim in this regard, he had information protected by professional secrecy, from which no one could release him, the judge said.

It was a heavy blow. But it was far from the worst for Daniel Jolivet.

Jolivet and St-Pierre were to have separate trials. But at the very last minute, the very day the jury was to be chosen to judge St-Pierre, his lawyer Danielle Roy received a call from prosecutor Jacques Pothier.

“Your client trusts us more than you, we’re going to represent him from now on,” he tells her.

In the greatest secrecy, while his lawyer prepared his case, St-Pierre had negotiated with the public prosecutor to obtain a contract of informer and a reduced sentence in exchange for his testimony against Jolivet.

The Crown no longer had only the confessions collected by the dubious Riendeau. She now had the best evidence possible: an accomplice, a direct witness to these sordid crimes…