Many political leaders want to leave a lasting legacy for the society to which they belong, whether by launching major development projects, by creating institutions called upon to play a fundamental role or by orchestrating far-reaching reforms in a area or another of community life. Some succeed.

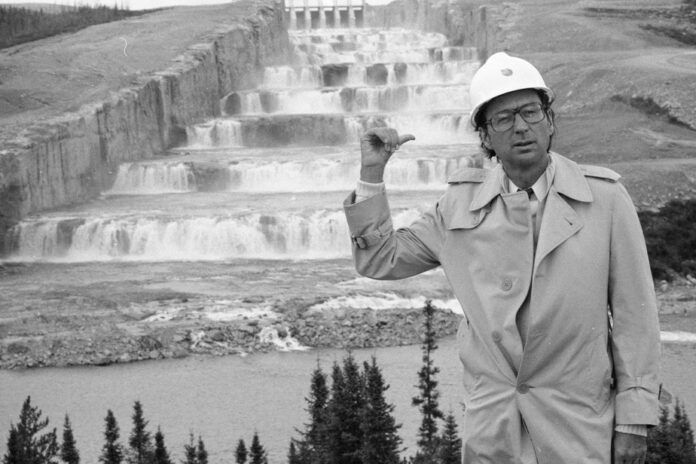

Premier of Quebec first elected in May 1970, Robert Bourassa unquestionably meets the definition of a great visionary. Recognized as the “father of James Bay”, this economist by training was deeply convinced of the value of hydroelectricity and the opportunity to develop the enormous energy potential of the great rivers of northern Quebec.

Launched during a political rally on April 30, 1971, some 50 years ago, the “project of the century” soon became the largest hydroelectric development project in the world then in progress, the La Grande complex.

It is important to emphasize that there was urgency: Hydro-Québec foresaw not being able to meet the winter peak of 1980 without the addition of new production capacities, whether nuclear or hydroelectric. However, many would have preferred nuclear power because it is quicker to build and commission than dams. In addition, the development of the Grande Rivière, more than 1000 km as the crow flies from Montreal, involved very significant risks, especially logistical and technical, and many unknowns. But Mr. Bourassa insisted, the commissioning schedule was accelerated, and Hydro-Québec management, led by Roland Giroux and Robert Boyd, finally agreed.

Responsibility for carrying out the work is entrusted to the Société d’énergie de la Baie-James, created expressly for this purpose. In order to quickly compose a highly qualified team, the personnel mainly come from two world-renowned engineering firms, Lavalin (now SNC) and the American Bechtel. The latter had notably been involved in the Churchill Falls megaproject, which was successfully completed on time and on budget. The idea of associating Bechtel with that of Baie-James, which came from Bourassa himself and his team, aims to reassure American financiers.

The project is part of a huge territory that is still virgin and not connected to the road network. A 620 km road must therefore be built to connect Matagami to LG-2, the first power plant to be built. In fact, a winter road from 1972, then a permanent road completed in three years… a feat in itself. This opening up of the James Bay territory now makes it possible to carry out other types of economic, mining and tourist activities. This was the dream behind the creation of the Société de développement de la Baie-James.

Very early on, a major obstacle called the project into question. The Crees and the Inuit, who had not been duly consulted, tried to block the project, both before public opinion and before the courts. This is how intense negotiations began with the Government of Quebec, which culminated in 1975 with the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, described as a model of its kind. In parallel, a vast environmental and social inventory is undertaken in order to better understand this new territory, its fauna, its flora, its ecosystems and the way of life of its occupants, and to mitigate the impacts of the project.

This kind of study will become the norm for any large project. Another unforeseen event, the devastation of LG-2 in 1974 tarnished the image of the project. The Cliche commission was quickly set up by the Bourassa government to shed light on labor-management relations and to recommend reorganization measures. Innovative conciliation mechanisms will be set up, and peace will return to the worksites.

René Lévesque, Premier of Quebec, presides over the ceremonies. Having had the delicacy to invite Robert Bourassa there, he took the opportunity to pay him a vibrant tribute. Father de la Baie-James, whom one of us accompanied, received this expression of gratitude with all the humility for which he was known.

If today Quebec can boast of having the cleanest electrical network in North America, if not the whole world, as well as some of the lowest rates, it is in large part thanks to the enlightened vision and to the audacity of Robert Bourassa. Estimated at 5 or 6 billion dollars on the basis of very preliminary studies, the La Grande Complex represented a colossal challenge. But, half a century later, the author of L’énergie du Nord, force du Québec won his bet hands down. We have every reason to be proud of this collective success, the benefits of which will still reverberate for many generations to come. Thank you, Mr Bourassa.